Authors:

Robert Muggah Principal, SecDev Group

Sameh Wahba Global Director, Urban, Disaster Risk Management, Resilience and Land Global Practice, World Bank

- Overlapping forms of inequality contribute to violent victimization in cities, from wealth inequality to educational opportunities and property rights;

- In virtually every city, the vast majority of violent crime is concentrated in just a few neighbourhoods;

- To reverse inequality and make cities safer, governments, business and civil society groups must start by targeting hot spots, especially in areas of deprivation.

Urban violence is predictable; it concentrates in specific places, among certain people and at very particular times. This means violence is hyperlocal, concentrated in “hot spot” neighbourhoods and blocks.

Inequality, whether in terms of income, wealth or welfare and endowments, is a strong determinant of everything from social cohesion and social mobility to life expectancy. A reduction of inequality and concentrated disadvantage in violent cities and neighbourhoods is, therefore, one of the most powerful ways to reduce violence.

Where a person is born and lives correlates with their overall life chances. Unsurprisingly, people living in environments characterized by high levels of economic and social inequality tend to be more exposed to violence and victimization than those living elsewhere. Neighbourhoods exhibiting higher levels of income inequality and concentrated disadvantage experience higher levels of mistrust, social disorganization and violent crime. Failure to adequately address these issues dramatically reduces equality of opportunity and outcomes across generations, perpetuating violence.

Multiple and overlapping forms of inequality contribute to violent victimization in cities. For example, people in the lower income-and-wealth quintiles are more likely to be a victim than those in the higher earnings brackets. In Mexico, despite a national decline in poverty and income inequality, municipalities registering higher economic inequality report higher levels of violent crime. The most-affected neighbourhoods tend to have limited natural surveillance, residential disadvantage (low-income, high unemployment, low education) and neighbourhood instability (high levels of mobility and single-headed households).

Similarly, racial and gender inequalities not only perpetuate economic inequality but are linked to higher exposure to violence. Labour force participation, educational achievement, reproductive health and political representation are all closely aligned with higher levels of safety.

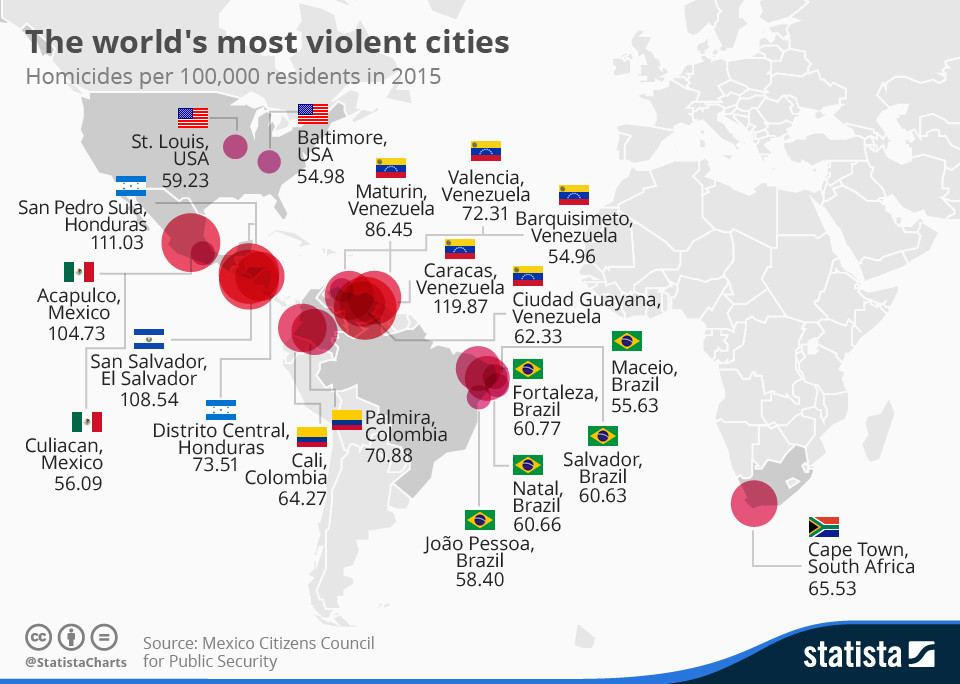

In virtually every city, the vast majority of violent crime is concentrated in just a few neighbourhoods. Some parts of a city may experience almost no violent crime, while in others it may be an order of magnitude higher. A study of five Latin American countries determined that 50% of all crime occurred in just 3-8% of street segments. In Bogota, for example, more than 98% of all homicides occur in less than 2% of its street segments.

Relationships between disadvantaged communities and local government – particularly law enforcement – are often fraught. When police use excessive force, this can further diminish trust. Moreover, when local residents exit violence-affected neighbourhoods, this can exacerbate socio-spatial segregation, erode social efficacy and intensify insecurity in the communities they leave behind. Meanwhile, neighbourhoods with higher levels of income inequality and more concentrated disadvantage experience higher levels of violent crime. There are frequently spillover effects from unequal and violent neighbourhoods into ostensibly more stable ones.

Fortunately, a growing number of cities around the world are prioritizing crime prevention and violence reduction. This is more radical than it sounds, as many local governments are understandably worried about acknowledging these challenges for fear it may negatively impact local and foreign investment, tourism and their legitimacy to voters. Cities from Medellin and Sao Paulo to New York and Oakland have achieved dramatic improvements in public safety and security over the past two decades. Likewise, global networks such as the Global Parliament of Mayors and Peace in Our Cities have encouraged members to dramatically reduce violence – by half – by 2030.

Lessons for reducing violence

1. Integrated urban upgrading must focus on hot spots: too often, city authorities either ignore or seek to contain poorer areas with police rather than prioritizing investment in affected neighbourhoods and tackling the determinants of criminal violence. The most at-risk areas frequently lack basic infrastructure and services and have poor spatial and digital connectivity with formal employment. Local residents often suffer from insecure land and property tenure and lack the education and life skills needed to access job opportunities. The absence of the state and a breakdown in the social contract can exacerbate violence, leaving poor and marginalized residents stuck in place.

2. Environmental design improvements and smart policing strongly correlate with reductions in urban violence. High-mast street lighting, for example, is credited with reduced crime and violence in informal settlements in Nairobi and an improvement in economic activities as retail outlets stay open later. The design of public spaces that are secure and accessible to various community members, the intelligent deployment of policing and resources to challenging areas together with strengthening community participation are also important. Problem-oriented policing is demonstrably effective.

3. Strengthening community engagement and collective efficacy is essential. Empowering neighbourhood residents to intervene on behalf of the public good is critical to reducing violent crime. This means building social cohesion, including the trust between residents and positive reciprocity with the government. Sharkey’s pioneering research in US cities underlines the value of working with young people to help them avoid violent confrontations and invest in positive pro-social behaviour and methods to avoid delinquent peers.

4. Improving access to jobs and life skills must be a priority. The creation of channels to decent jobs for youth in high-violence neighbourhoods is effective in reducing delinquency and crime. Strategies that also support access to jobs and life skills development for specific at-risk young males (and their parents) are also needed. The goal is to offer opportunities and perspectives for at-risk youth that offer pathways away from violence.

Ultimately, urban crime and violence have far-reaching economic costs. For example, a study of US cities determined that a 25% reduction in homicidal violence could lead to a 2.1% increase in housing prices the following year. This translates into gains of between $1.5 billion in Jacksonville to $11 billion in Boston. Tackling inequality – of income, access to opportunity and human capital – not only makes sense morally and ethically but economically too.

To reverse inequality and reduce crime in cities, governments, business and civil society groups must start by targeting hot spots, especially in areas of deprivation. Comprehensive interventions that combine smarter infrastructure, data-driven policing and targeted service delivery with environmental design improvements and greater security over property tenure are critical. Programmes that empower and engage communities and improve their access to life skills and economic opportunity are also vital. When these policies are in place, they can deliver rapid and lasting results. Reducing inequality is a down payment on violence reduction in the long-term.

Instead, city governments, the business community, and civic leaders need to make violence reduction a priority. What is required is an integrated approach to tackle spatial, economic and social exclusion. This includes comprehensive urban upgrading to address those issues faced by locals.

Original source of article is from the World Economic Forum https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/03/what-are-the-causes-of-urban-violence-inequality/